“That moment when I whirl with words is a space

of transgression [and] I write to live”.[1]bell hooks, (1995), Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work. H. Holt., p. 45.

bell hooks

1952-2021

African-American author, feminist, educator and social activist

The daily with Uncle Malcolm

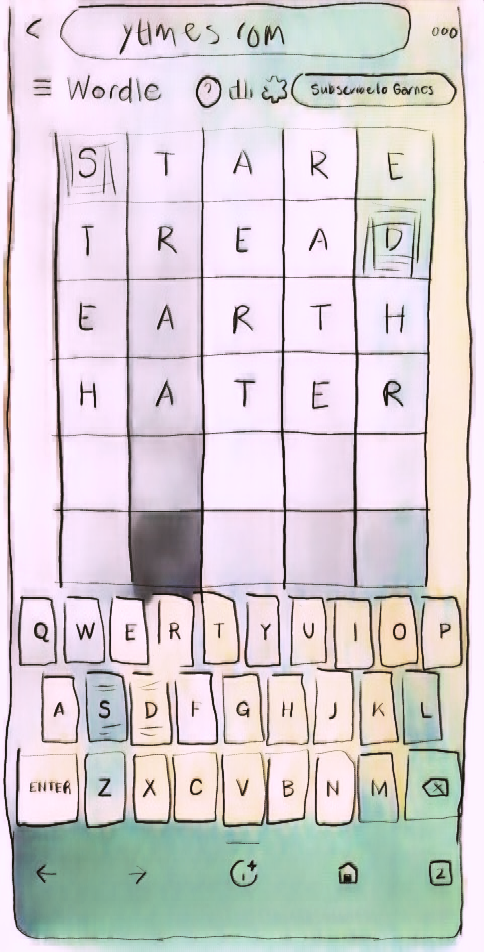

“An unusual combination of letters that gave me quite a spin”, Uncle Malcolm tells me as he explains his 5 out of 6 Wordle results today.

The five-letter, six-guess word game which began as a love story and today has over 2 million players, offers a linguistic challenge and a point of everyday connection between people. Like many families and friends around the globe, Uncle Malcolm and I have been texting our daily Wordle efforts with one another since Tuesday 22 March 2022 for a total of 652 days of Wordling together. If the day draws to a close without the daily share, inevitably one of us will text, “Are you OK?”, a check in inspired by the real life story of 80-year old Illinois resident Denyse Holt—alarm was raised by her two daughters when she failed to text her daily Wordle whereupon a visit by Denyse’s neighbour found her locked in her basement after being woken up by a naked, knife-wielding intruder in the middle of the night.[2]Read the full story in The Guardian here. Needless to say, Uncle Malcolm and I always share our attempts, sometimes provide one another with a behind the scenes screenshot of the completed grid and send a hand clap emoji for a particularly valiant effort.

The pattern our words make is always a talking point.

“Out of the gates strong and decided to stretch my legs into a 5!” I say.

“A great idea. Why finish in 2 when you can make it all last for 5? And you produced a wonderful field of orange, without the slightest hint of a blue!” Uncle Malcolm says,

Uncle Malcolm indulges his first love of numbers as we share our latest Wordle data.[3]My Uncle Malcolm is not just my favourite Uncle, he is also a fabulous maths educator. Before I stepped into the academy, Uncle Malcolm was already there working as a senior lecturer in the … Continue reading

“Nothing like stats on a Saturday morning—my average is now 3.628!”, I say.

“I have three averages—3.836, 3.880 and 3.916”, Uncle Malcolm says, “I like the first one best, which I get from dividing by my total number of games (which is really a cheat). The second one is by dividing by the total ‘wins’ (which also is cheating because I’m ignoring the games where I bombed out). The last one is only an estimate but probably the most accurate (and most honest), where I’ve given my fails a score of 7”.

And we delight in deconstructing our Wordle strategy.

“It’s interesting how the small variation in our start words led us down quite different paths then pulled us back to the solution”, Uncle Malcolm says.

“It sure is! I’ve been using STARE as a starting word for ages now—I rarely stray from it”, I say.

“I think STARE is a great starter. R S T keep appearing”, Uncle Malcolm says. “I do something similar, but I’m frightened about getting into a rut so use a group of words—slate/steal etc, raise (but that’s not as reliable), spare/spear, share. Maybe I should try just the same one and risk becoming boring 😮”.

There are days when we consider for a while the curious origins of words and the strangeness of the English language, question the use of slang and every so often shake our fists in frustration at five letter words with double—or even worse, triple—letters and American spelling. And then; perhaps because we are in the daily habit of chatting; perhaps because words are always playing about with experiences, emotions and those who have them; perhaps because we are far away and Wordling closes the gap; there are moments when words of worry about our lives and loves spill over into the world of Wordle. Words are like that, full of echoes and memories[4]On the 29th of April 1937, Virginia Woolf spoke on BBC radio in a series called “Words Fail Me”. Her talk was titled “On Craftsmanship” and here she laid out her thoughts on … Continue reading, flashing this way then that to maintain their liberty of meaning while holding on tight to the relationships between them, drawing us closer and closer still to how things are, creating events [5]Ursula Le Guin (2016, Words are My Matter: Writings about Life and Books, p. 113) wrote beautiful about the way in which words “do things” in the world as did Susan Sontag (“The … Continue reading and asking us to consider how we feel about them.

“A word after a word is power” – Canadian writer Margaret Atwood next to her Canada Post special stamp in her honour, in Toronto on 25 November 2021. Photo: Nathan Denette, The Canadian Press.

Take my hand and do-si-do

It doesn’t feel like coincidence that while thinking about what I might write for the first In-sister post for 2024, I am reading Margaret Atwood’s recent collection of essays and occasional pieces Burning Questions [6]Burning Questions represents Atwood’s third anthology of essays and miscellaneous pieces. The first collection, Second Words (1960-1982) is an anthology of her book review publications, Moving … Continue reading and the Wordle answer for game #928 is TWIRL. A combination of the words “twist” and “whirl”, “twirl” embodies what it is that I think writing might be and do. Held tightly in its embrace, writing that twirls spins two or more ideas together, makes space for thinking and wondering to circle each and the other, rapidly stirring and turning across the blank page to throw wide open possibilities we have not yet imagined. Both “twist” and “whirl” do-si-do back-to-back between shadow and sunshine, and what a time they have, sashaying as they do within the five-step rhythm of a single “twirl”.[7]This sentence is inspired by the poem by Mary Oliver, (2017), “We Shake with Joy”, Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver, Hatchette Books, p. 70.

I have been searching for some time for a word to describe Margaret Atwood’s non-fiction writing style and “twirl” seems very fitting. Reading the non-fiction work of a fiction writer, as Atwood suggests, is not only an uttering but an “outering” of the shadowy thoughts and feelings that sit behind the stories they write and enables us as readers to hold them “up to the light where we can take a good look at them”.[8]Margaret Atwood, Burning Questions, p. 13. In Burning Questions, Atwood turns around her responses to books and authors she loves, the social and political issues that stand to impact upon the people she loves, and the love she has sustained for words in a writing career spanning more than 50 years. Her pieces are unguarded and unapologetic, furious and feisty, tender and touching; and my personal favourites are those which speak to the sensibilities of in-sister—“From Eve to Dawn” (a telling and timely review of Marilyn French’s life work to expose the violence of patriarchy), “Anne of Green Gables” (where the seeds of my own rebellion were planted while dreaming of frilled sleeves and flounced skirts), “Am I a Bad Feminist?” (a question many of us constantly ask which leads to another, what makes someone a good feminist?), and, “We lost Ursula Le Guin when we most needed her” (because if there is any truth to be found it is in the pro-foundly sane, smart, crafty and lyrical voice of U.K.L).[9]Here are the references for these essays in Burning Questions: “From Eve to Dawn” (pp. 21-25), “Anne of Green Gables” (pp. 83-91), Am I a Bad Feminist?” (pp. … Continue reading

If only a dazzling dress!

As a writer of non-fiction prose, Atwood ensures she wears the appropriate outfit to twirl the content of each piece together. In “Buttons or bows?” she remembers “a strapless pink tulle formal with a bodice studded with fake seed pearls” [10]Burning Questions, p. 267. she made in 1956 to wear to a dance and as I read her work, I imagine the hem floating above her knees as she glides effortlessly from one idea to the next, as light as air and with as much weight as needed to convey her message. The essay sashays between the necessity of paying attention to the fictional clothing of characters to ensure authenticity, the development of her material identity linked explicitly to playing dress-ups with Hollywood paper-dolls, her prowess with a sewing machine, and a heartfelt declaration to “Bring on the fairy godmothers!” if a dazzling dress was all it might take for our writing and ourselves as women to truly shine.[11]Burning Questions, p. 266.

I dream of becoming a vaudeville dancing girl like my great-grandmother Margaret and join this Margaret in a similarly fancy frock – deep mauve with a sequined bodice, ostrich feathered straps and a skirt made of sheer voile. Under the spotlight, together words and I shall twirl about in a blaze of writing that shimmers, singing at the top of our lungs, “My star is on the ascendant!”[12]This line from the song “I don’t care!” was first sung by arguably the most famous Canadian vaudeville performer, Eva Tanquay in 1905. Tanquay was beautiful, brazen and delighted in … Continue reading After all, “we may not be what we are, but what we wear is a handy key to who we think we are”[13]Burning Questions, p. 270. and in the world of the working class, “you’ve got to dance with them that brung you”.[14]Brené Brown, (2015), Rising Strong, Vermilion, p. 251.

“Dancing girls”, a short story by Atwood in an anthology of the same name, tells of aspiring architect Ann wishing she had been able to see the dancing girls invited to the party hosted by a First Nations man in the apartment next door. Taking a regretful walk through the streets of Toronto, Ann thought about her dream of creating future and perfect green spaces and knew it was cancelled in advance.[15]Margaret Atwood, (1978), Dancing Girls and Other Stories, Seal Books, p. 226. Ann does not get her fairy tale ending and as readers we are left to twist and swirl about in the wake of Atwood’s reality check. Recognising the truth of a situation is in fact one of Atwood’s golden rules of writing—“Nobody is making you do it: you chose this”, she insists. Choice is a flitting thing[16]I have adapted this phrase from Emily Dickinson’s poem, “Opinion is a flitting thing” #1455, in The Complete Poems, of Emily Dickinson, (1960), TJ Books, p. 617. and like any truth, there are various slants to this one which put our choice to write in light and shade in equal measure.

“Surprising!” Uncle Malcolm says of today’s Wordle. “It’s not a word form I would have thought of”.

Yes, I think to myself, the twisting and swirling circuit letters take to form words are indeed, as Emily Dickinson tells us, truth’s superb surprise[17]Emily Dickinson, (1960), “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” #1129, The Complete Poems, of Emily Dickinson, TJ Books, p. 506.. For the record, I am grabbing onto this unexpected turn with Margaret Atwood with both feet. I am choosing to dress my writing in a soft yet spangled purple party frock, step it across the orange pile carpet to the HMV player in the corner of the lounge room, find the groove of “Dancing Queen” on a vinyl version of ABBA Arrival and give my writing permission to twirl.

References

| ↑1 | bell hooks, (1995), Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work. H. Holt., p. 45. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Read the full story in The Guardian here. |

| ↑3 | My Uncle Malcolm is not just my favourite Uncle, he is also a fabulous maths educator. Before I stepped into the academy, Uncle Malcolm was already there working as a senior lecturer in the Aquinas School of Education at the Australian Catholic University campus in Ballarat. I do some google scholar searching and find a paper presented by Uncle Malcolm at the joint Educational Research Association and Australian Association for Research in Education conference in Singapore in 1996 titled “Children’s information computation methods“. What I loved about this paper (aside from the prose, problem and project reported) is the way in which Uncle Malcolm places value on the ways of being, knowing, and doing that primary school children bring with them to maths, adn that these can be a starting point for further learning. In this regard, I think our fields of research are not quite as disparate as they first seem—both of us find a sense of magic in the ways in which young people make meaning in, from and through the world. |

| ↑4 | On the 29th of April 1937, Virginia Woolf spoke on BBC radio in a series called “Words Fail Me”. Her talk was titled “On Craftsmanship” and here she laid out her thoughts on the use of words. Just eight minutes remain of what is believed to be the only surviving recording of Virginia Woolf’s voice and you can listen to an excerpt of the recording here:https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20160324-the-only-surviving-recording-of-virginia-woolf. The piece was later published in Virginia Woolf: Selected Essays (2008, pp. 85-94) and it is a playful and poignant discussion about the “craft of words”. |

| ↑5 | Ursula Le Guin (2016, Words are My Matter: Writings about Life and Books, p. 113) wrote beautiful about the way in which words “do things” in the world as did Susan Sontag (“The Conscience of Words”, in At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches, 2007). |

| ↑6 | Burning Questions represents Atwood’s third anthology of essays and miscellaneous pieces. The first collection, Second Words (1960-1982) is an anthology of her book review publications, Moving Targets compiles materials from 1983 to the mid-2000s, and Burning Questions spans from mid-2004 to mid-2022. Each collection encapsulates roughly two decades of Atwood’s work, each piece a time stamp. Her gracious, generous, poignant, sharp, frank and tongue-in-cheek style challenges as it cajoles—I loved Burning Questions as much as I have all of her other work. Margaret Atwood, (2022). Burning Questions: Essays and Occasional pieces 2004-2021, Chatto & Windus, pp. xiii-xx. |

| ↑7 | This sentence is inspired by the poem by Mary Oliver, (2017), “We Shake with Joy”, Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver, Hatchette Books, p. 70. |

| ↑8 | Margaret Atwood, Burning Questions, p. 13. |

| ↑9 | Here are the references for these essays in Burning Questions: “From Eve to Dawn” (pp. 21-25), “Anne of Green Gables” (pp. 83-91), Am I a Bad Feminist?” (pp. 335-339), and “We Lost Ursula Le Guin When we Most Needed Her” (pp. 340-343). |

| ↑10 | Burning Questions, p. 267. |

| ↑11 | Burning Questions, p. 266. |

| ↑12 | This line from the song “I don’t care!” was first sung by arguably the most famous Canadian vaudeville performer, Eva Tanquay in 1905. Tanquay was beautiful, brazen and delighted in displaying and playing with her femininity and sexuality on stage. The song embodies her determination to do whatever she liked, the devil be damned. For more, see The Queen of Vaudeville: The Story of Eva Tanquay, by Andrew L. Erdman, 2012. |

| ↑13 | Burning Questions, p. 270. |

| ↑14 | Brené Brown, (2015), Rising Strong, Vermilion, p. 251. |

| ↑15 | Margaret Atwood, (1978), Dancing Girls and Other Stories, Seal Books, p. 226. |

| ↑16 | I have adapted this phrase from Emily Dickinson’s poem, “Opinion is a flitting thing” #1455, in The Complete Poems, of Emily Dickinson, (1960), TJ Books, p. 617. |

| ↑17 | Emily Dickinson, (1960), “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” #1129, The Complete Poems, of Emily Dickinson, TJ Books, p. 506. |

I love this! Thank you for sharing.

Thank you Donna – it’s funny how I often turn to Margaret Atwood at the beginning of each year to think anew about writing – definitely my go to gal!