“Happiness is the reflection of a smile”, from Holly’s words of wisdom: An appointment calendar for 1977.

Hello Holly Hobbie

I didn’t know anything about her except that her name was Holly Hobbie, and she was the first to keep my secrets close in a white diary. Holly Hobbie, an American writer, water colour artist and illustrator, created and sold her namesake as artwork to American Greetings in the late 1960s. Originally referred to as the “blue girl”, Holly Hobbie’s distinctive carefree and rustic dress of patchwork frocks and denim jeans, often overlaid with a practical full length calico apron and fly-away hair tucked under a cotton bonnet, had instant appeal – she represented all that was good, wholesome and light in the world. Holly Hobbie worked with the Humorous Planning department at American Greetings who saw the commercial potential of “blue girl” merchandise and Holly Hobbie rag dolls, fabric, furniture, ceramics, and stationery were soon licensed and available for purchase.

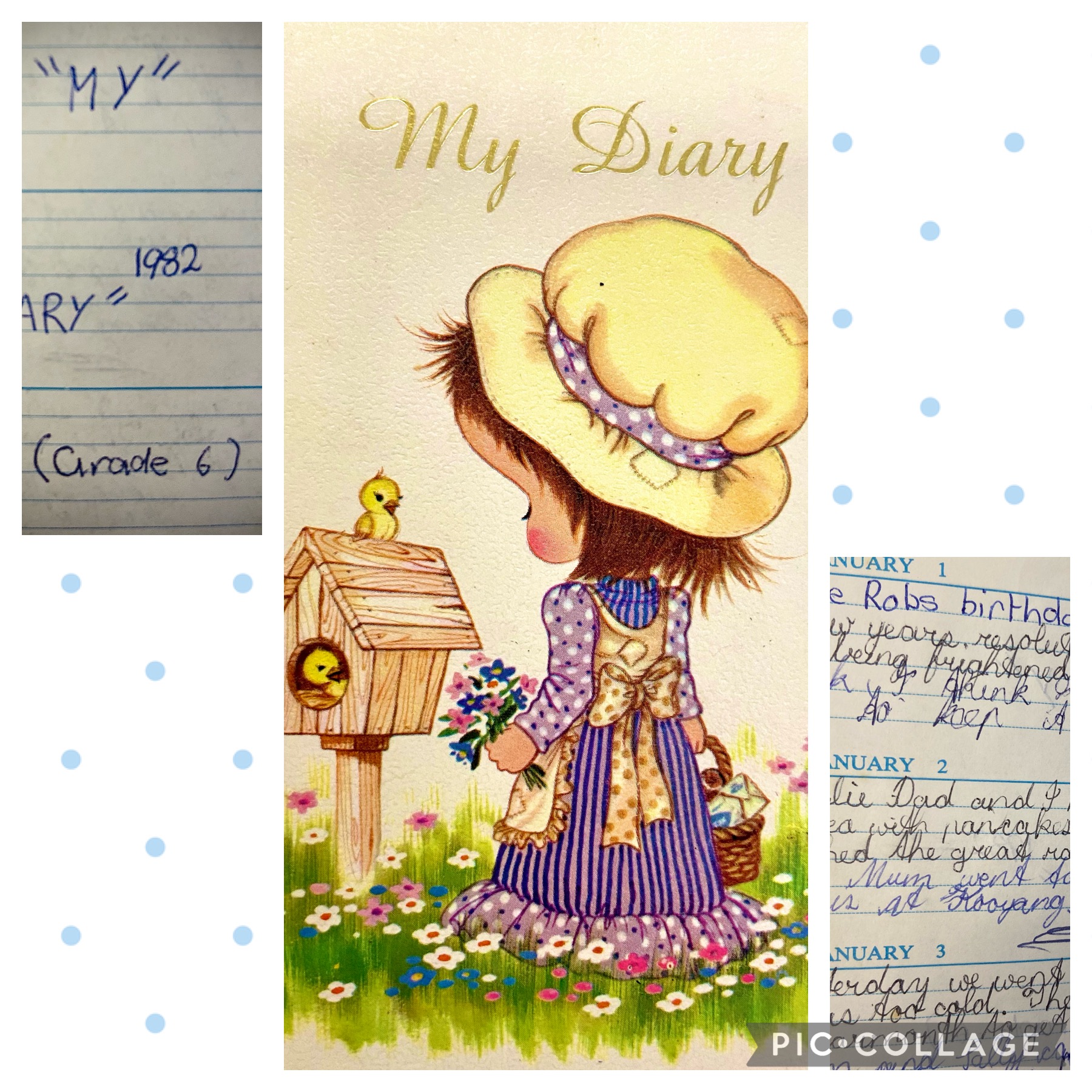

Like many young girls, I was in love with Holly Hobbie, and she was my best friend. I collected Holly Hobbie swap cards and I played Holly Hobbie with my other friends during lunchtime at school. When I ventured down to the pond at the bottom of the pine forest in search of magick and pixies under the mushrooms, I imagined my raggedy pinafore, floppy bucket hat and slightly too big gumboots made me look just like her. My first Holly Hobbie notebook was small, hardcover, and white with the words “My Diary” stamped in gold cursive script on the front, but she wore purple not blue. Holly is pictured carrying a small posy of pale pink and blue flowers in her left hand, and a wicker basket in her right. Her long-striped dress is adorned with polka dotted sleeves, a large, flowered frill on the bottom edge and she has on her trademark cream coloured apron. Her short, brown, and very straight hair sticks out in all directions from underneath her matching bonnet and her cheeks are flushed red. Two fluffy yellow chicks sit on a wooden letter box to greet her, but her back is slightly turned, and Holly’s eyes are cast down. The fresh green grass at her feet is carpeted with blue, pink, and white daisies.

Dear Bessy

I wrote my first diary entry on 1st January, 1982 when I was ten years old. I didn’t know then that I was following a literary tradition of young women writing diaries—Louisa May Alcott began writing a diary too when she was 10, Anaïs Nin and Sylvia Plath were 11, and bell hooks started to pen her personal accounts of life as a teenager. I remember I had begun reading Anne Frank’s The diary of a young girl over thesummer—her musings about the oddness of a 13 year old keeping a daily journal and the early confession of wanting to write to “bring out all kinds of things that lie buried deep in my heart” (p. 2), were all I needed to begin.

Holly Hobbie’s diary provided a structure to enter my daily reflections—each page was divided into three, with an allocation of five lines of writing which, with my large and uneven copperplate script, allowed me to write on average 26 words per entry. Anne Frank begins her diary entries with “Dearest Kitty”, and mine begin (now and then) with “Dear Bessy”. “Bessy” is close enough to Bethy, the name I am fondly called by close family and also references my Dad’s beloved steel-grey V8 Ford Fairmont he affectionately referred to as “Bessy”. In words which alternate with black and blue ink, my very first entry reads, “my new years resolution is to stop being frightened of the dark, I think I’ll be able to keep it”. The monsters that terrified Anne Frank were real and visible in broad daylight; mine were imagined and only appeared in the shadows when the lights went out.

I must be a mermaid

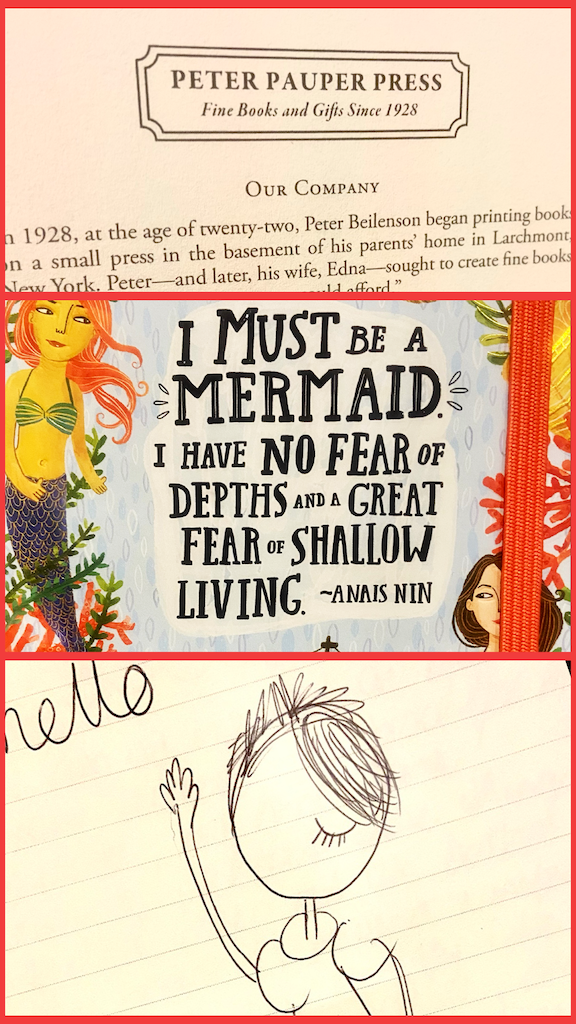

My acute fear of darkness remains and while there are some temporal gaps, the practice of writing in a journal has stayed with me. Now, I only ever use a black ballpoint pen, I systematically write on one ruled page leaving the other blank, and my preference lately is to write in Peter Pauper Press notebooks—the pages are archival and acid-free, they have a paper pocket at the back for keepsakes, and a matching elastic band place holder. Attracted to the aesthetics of a “traditional” black notebook, I used to only buy red, pink—and when I was lucky enough to find them, purple—ruled Moleskins, but now I like the sentiments attached to this family run stationery company. Peter and his wife Edna proudly state on the inside of every journal that they seek to create fine books replete with “beauty, quality and value” sold at “prices even a pauper could afford”. The journal I am writing in now features Lauren Lowen’s playful illustration of one blue tailed and one red tailed mermaid hovering over a sailing boat on the sea, singing in harmony the words of Anaïs Nin, “I must be a mermaid [Rango]. I have no fear of great depths and a great fear of shallow living” (The four chambered heart, 1959, p. 18).

My acute fear of darkness remains and while there are some temporal gaps, the practice of writing in a journal has stayed with me. Now, I only ever use a black ballpoint pen, I systematically write on one ruled page leaving the other blank, and my preference lately is to write in Peter Pauper Press notebooks—the pages are archival and acid-free, they have a paper pocket at the back for keepsakes, and a matching elastic band place holder. Attracted to the aesthetics of a “traditional” black notebook, I used to only buy red, pink—and when I was lucky enough to find them, purple—ruled Moleskins, but now I like the sentiments attached to this family run stationery company. Peter and his wife Edna proudly state on the inside of every journal that they seek to create fine books replete with “beauty, quality and value” sold at “prices even a pauper could afford”. The journal I am writing in now features Lauren Lowen’s playful illustration of one blue tailed and one red tailed mermaid hovering over a sailing boat on the sea, singing in harmony the words of Anaïs Nin, “I must be a mermaid [Rango]. I have no fear of great depths and a great fear of shallow living” (The four chambered heart, 1959, p. 18).

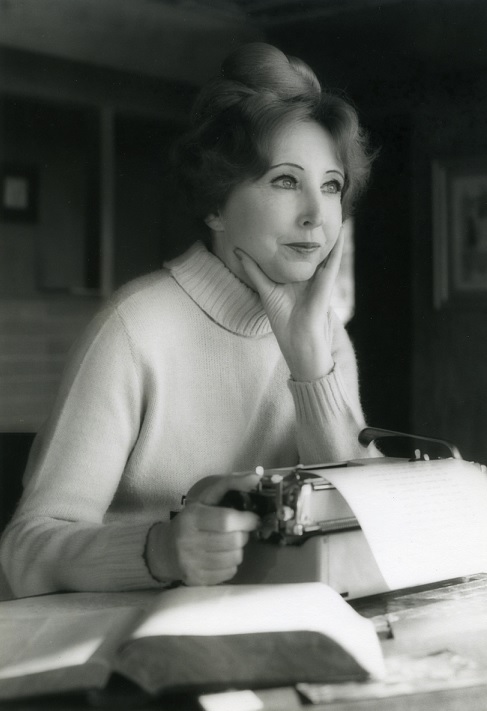

I catch the line of Anaïs Nin’s words to the novel which threads its way to her unexpurgated journals. Anaïs Nin’s diaries represent a 63 year long process of endlessly unrolling the ribbon, unfolding the petals, and exposing all the multiple layers of a self in order to reconstruct who she was and wanted to become on her own terms. She lived a wild, impassioned, and uncensored life and as Kim Krizan notes, “did things that few of us would admit—or even consider”. In the late 1960s she was revered as a feminist icon for the personal account she provided, without apology, of how to make it as a female writer in a man’s world. By the 1990s she was denounced as a “stupid slut” who had “lied and fornicated the way the rest of us breathe”, but today, the online world has made room for an Anaïs Nin philosophical and poetic revival.

We don’t see things as they are, we see things as we are.

And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.

Ordinary life does not interest me.

We write to taste life twice.

Shame is the lie someone told you about yourself.

Had I not created my whole world, I would certainly have died in other people’s.

The words of Anaïs Nin are available to us in ways she could never have imagined but I sense she would have wanted us to kiss them gently on the lips and taste the wonder and mystery of meaning to be found there.

Writing, life—in diaries

I am continually drawn to what women say in their diaries about writing, what they say about diary writing in particular, and what they say about the ways in which writing both makes living possible. On a Sunday in late 1843, 10-year-old Louisa May Alcott shared in her diary how much she enjoyed writing in her “imagination book”. Life, she reflected, was more pleasant than it used to be as a result, and she did not care about dying any more for her mind was happy. Anaïs Nin described her diary as the place where her drifting and dissolving self might become whole again (The diary of Anaïs Nin, Volume 2, 1934-1939, p. 102) and further that writing secretly and subterraneously in her diary was a “writing which is not writing but breathing” (p. 106).

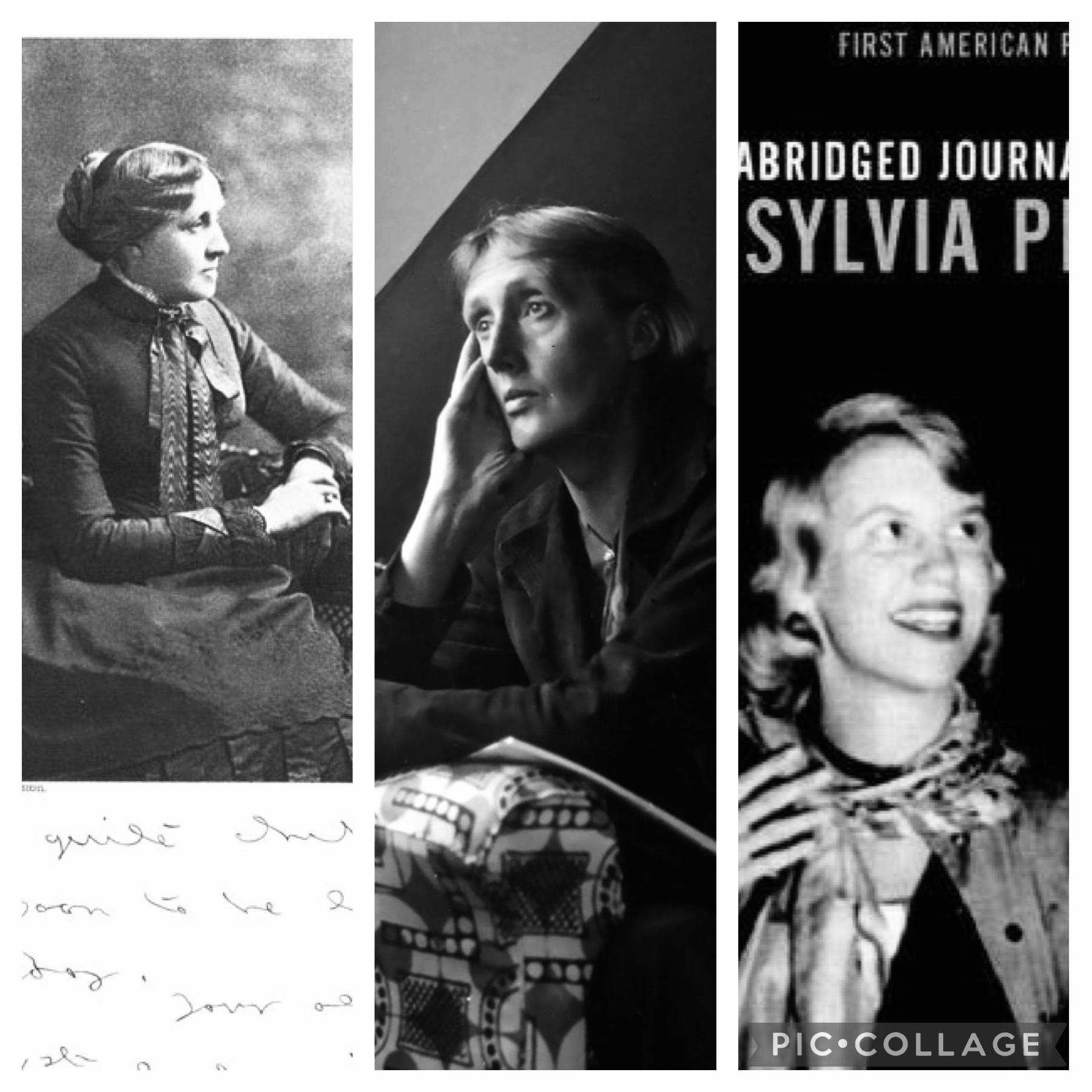

At precisely ten minutes to 11am on Friday 8th April 1921, Virginia Woolf described her diary as a “kindly blankfaced old confidante”, “loose knit…and so elastic it will embrace anything”, a place to breathe where stray matters of life might accidentally be swept up and found later to be the “diamonds of the dustheap” (A writer’s diary, 1953, p. 11). Sylvia Plath described the “virginal, white” page of her diary as a “warmup” and a “directive” to write. “All I need to do is work” she explained, “break open the deep mines of experience and imagination, let the words come and speak it all, sounding themselves and tasting themselves”[1]. Plath felt deeply that words enabled her to “stay the flux of life” (The unabridged journal of Sylvia Plath, 2000, p. 283). “Writing”, she wrote, “breaks open the vaults of the dead and the skies behind which the prophesying angels hide” (p. 268) and Plath drew inspiration from “blessed” (p. 286) Virginia Woolf’s practice of observing passing moments every day— “each day an exercise or a stream of consciousness ramble” (p. 304) in order to “speak my deep self…and speak deeper still” (p. 286).

Mary Moffat and Claire Painter tell us in their edited collection of the diaries of 33 women, Revelations: Diaries of women, that women keep diaries to pen and puzzle out on any given and quite ordinary day, their confusion and dissatisfaction with the way love, work and relations of power have been laid out for them alongside a sense of self-significance and inner strength. “The diary became the place where she could escape these definitions and let the real self have its day” (p. 6), they write, by asking “Who shall I be?” (p. 8) In March 1846 at the tender age of 13, Louisa May Alcott wrote that while she was old for her age, didn’t care much for girl’s things, and people thought her wild and queer, she had made a life plan to be “good”.

Approaching middle age Virginia Woolf mused in her diary that “life is, soberly and accurately, the oddest affair…I used to feel this as a child—couldn’t step across a puddle once, I remember ,for thinking how strange—What am I?” (30 September 1926, p. 101). Some years later she resolved to hold no illusions of ever being famous or great but instead to “go on adventuring, changing, opening my mind, and my eyes, refusing to be stamped or stereotyped” (29 October 1933, p. 213). While a student in college, when Sylvia Plath thought of her future, she saw herself as a “White Queen who had to run like the wind to remain in the same spot” and asked, “Lord, what will I be? Where will the ceaseless conglomeration of environment, heredity and stimulus lead me?” (p. 24). She planned never to be constrained by any role and insister-ed,

Never will there be a circle, signifying me and my operations, confined solely to home, other womenfolk, and community service, enclosed in the larger worldly circle of my mate (p. 105).

As a young woman Anaïs Nin too saw her diary writing as an explicitly feminine activity – personal, personified and positioned in opposition “masculine alchemy”. She feared becoming a product of the patriarchal machine and insister-ed that the diary must continue if she were to “remain on the untransmuted, untransformed, untransposed plane” (p. 172).

Louisa May Alcott, Virginia Woolf, Anaïs Nin, and Sylvia Plath were strong women, smart women, struggling women, sensitive women who wanted to write the world on their own terms. Reading their diaries, I continually see fragments of me in all of them, and find myself returning to my own diaries to search for pieces that somehow got lost along the way. I also find myself reading work by women writers in search of the same and lately, I have been floating through the fiction writing of Alice Hoffman. Hoffman writes often about life as women, about how real life as women can be hard life, and about how women find a way through real and hard life by drawing on histories, knowledges, practices, relationships, and sense-abilities as women. I love her work and intended this piece, “White diary” to be about her book Blue diary. But, once I began writing, I found that I was “flown”, as Virginia Woolf would say (A writer’s diary, 1953, p. 89), with too many words about diaries, and women writers, and women writing that, I needed to slow down. I didn’t know I had this much to say about diaries but now that I do, I am going to interlace this white braid of thinking and wondering with two more threads—blue diary and purple diary.

i look forward, with joyful expectation, to more diary talk xxx i keep a ‘gratitude writing and creativity journal’ and this work has inspired me to write in her more often. Thanks again.