Just write, just write, just write

I am reading Natalie Goldberg’s Writing down the bones: Freeing the writer within—well actually, I’m listening to her read it to me. Mostly on my way to work as company during the four-hour round car trip there and back, sometimes when I am out walking in the quiet hours before dawn with Dolly, my ageing Maltese Shih-tzu, as company. Natalie has the broadest New York Jewish accent, there is a smile in the way she speaks, and every now and then a soft belly laugh erupts in the space between her sentences. I love the sound of her voice—drawing me in to remember writing, calling me to remember what it is to write, and reminding me why I like writing. She says things like,

“Whatever is in front of you is a good beginning” (p. 31).

“It won’t begin smoothly. Allow yourself to be awkward. You are stripping yourself” (p. 39).

And she says,

“Writing practice softens the heart and mind, helps to keep us flexible so that rigid distinctions between apples and milk, tigers and celery, disappear. We can step through moons right into bears” (p. 37).

I think about white ink flowing like milk from my bones and mingling with flesh and blood hearts fallen from an apple tree to seed strawberry fields of words soon to blossom into new worlds.

“Handwriting is more connected to to the movement of the heart” (2016, p. 7)

“Print is predictable and impersonal, conveying information in a mechanical transaction with the reader’s eye.

Handwriting, by contrast, resists the eye, reveals its meaning slowly, and is as intimate as skin” (2013, p. 12).

Then she says,

“Hear ‘you are boring’ as distant white laundry flapping in the breeze” (p. 28).

And I lay down on the lush green patches of phrases and paragraphs to watch the sky writing of clouds pass by.

She also says,

“Ovens can be cantankerous sometimes, and you might have to learn to ways to turn your heat on” (p. 51).

My right hand bears the scars of sliced up sentences that scorched as they surfaced.

“Come to love the details and step forward with a yes on our lips” (p. 49)

“Just sing and write in tune” (p. 59).

“Just write, just write, just write” (p. 101) she says.

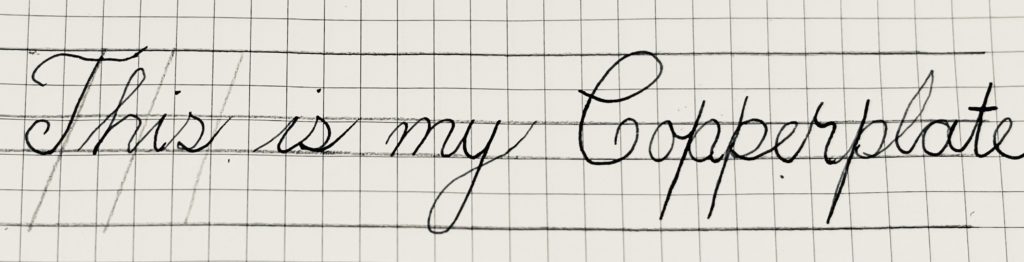

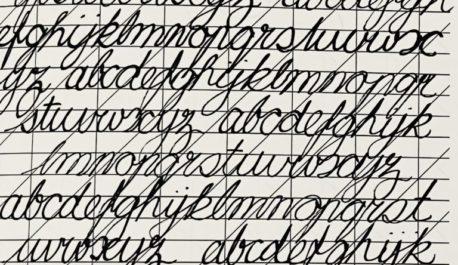

With Natalie’s voice resonating from my ears through my entire body, I am itching all over to pick up a pen. And so here I am at 6:30am sitting cross-legged at my desk in my purple chiffon baby doll dress and pale pink denim jacket watching early morning travellers depart to exotic destinations out of my office window and scratching words on the page, keeping my hand moving and just writing. Natalie says she fills a notebook a month with handwriting. Even if she’s only written two pages with two days to go, she picks up her pen and gets busy. I love writing in my journal, I love the process of pen in handwriting on the page, just writing. Typing on a keyboard click clacks a fast staccato rhythm, mesmerising meaning with each finger strike into “block, black letters” (Goldberg, 2016, p. 7). Handwriting is different—handwriting curls into curves at an entirely different pace. Right now, as I’m writing, my hand is starting to cramp, just across the top of my knuckles on the left-hand side. I’m out of practice and my handwriting is out of shape, struggling to keep up with the words pushing and pulling for release. I watch them run from my pen onto the page, poor little darlings, a little bit messy, a little bit misformed, a little bit willful as they merge into a less than elegant style that only I can read. Snips and snaps of learning how to handwrite memories sidle up beside me. At first I see oversized and clumsy attempts at block script, which soon move to running writing in cursive. I see the earnestness of my letters reflecting a young girl who knew there were rules she had to conform to—tops and tails, dots and crosses that must be placed in the correct place, just so—while yearning to allow her hand to run wild with all manner of fancy.

Then something happened and I owe it all to Mrs Edgar. EDGAR Margaret 26.02.1941 – 05.08.2016. Dearly loved wife of Jim. Loved and loving mother of Stephen, Elizabeth, and Paul; cherished grandmother of all her grandchildren; and much adored Grade Five teacher librarian. All my classes that year were held in the library with Mrs Edgar, surrounded by and in the company of books. Lying on one segment of a brightly coloured and cushioned child size book worm we had made, she read all the classics to us, and pronounced words beginning with “wh” in a whisper. I think I spent more time on that bookworm than I did at my desk that year, listening to her read and flying away to other fictional worlds on my own. When Mrs Edgar announced that she was going to teach us how to write in copperplate, I was not surprised—it seemed only fitting that such an elegant and educated woman knew how to write in an equally elegant and educated hand.

Handwriting with a flourish

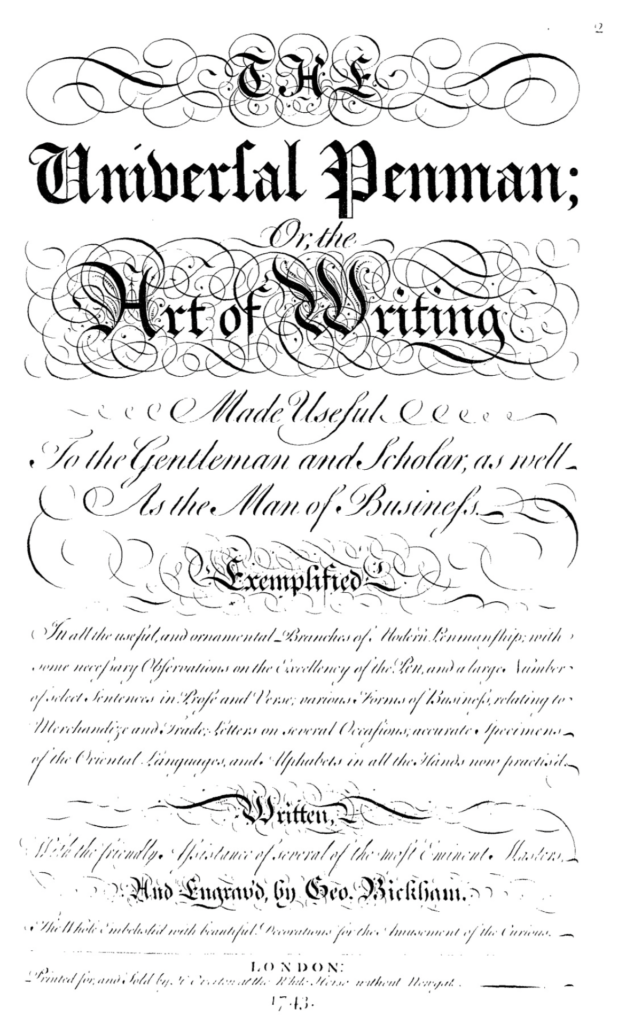

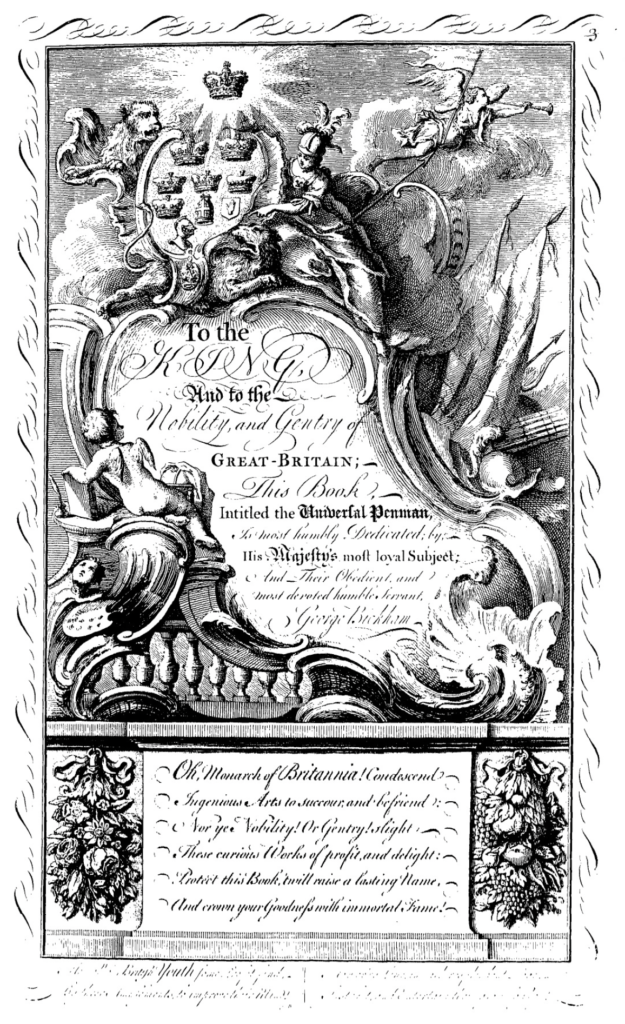

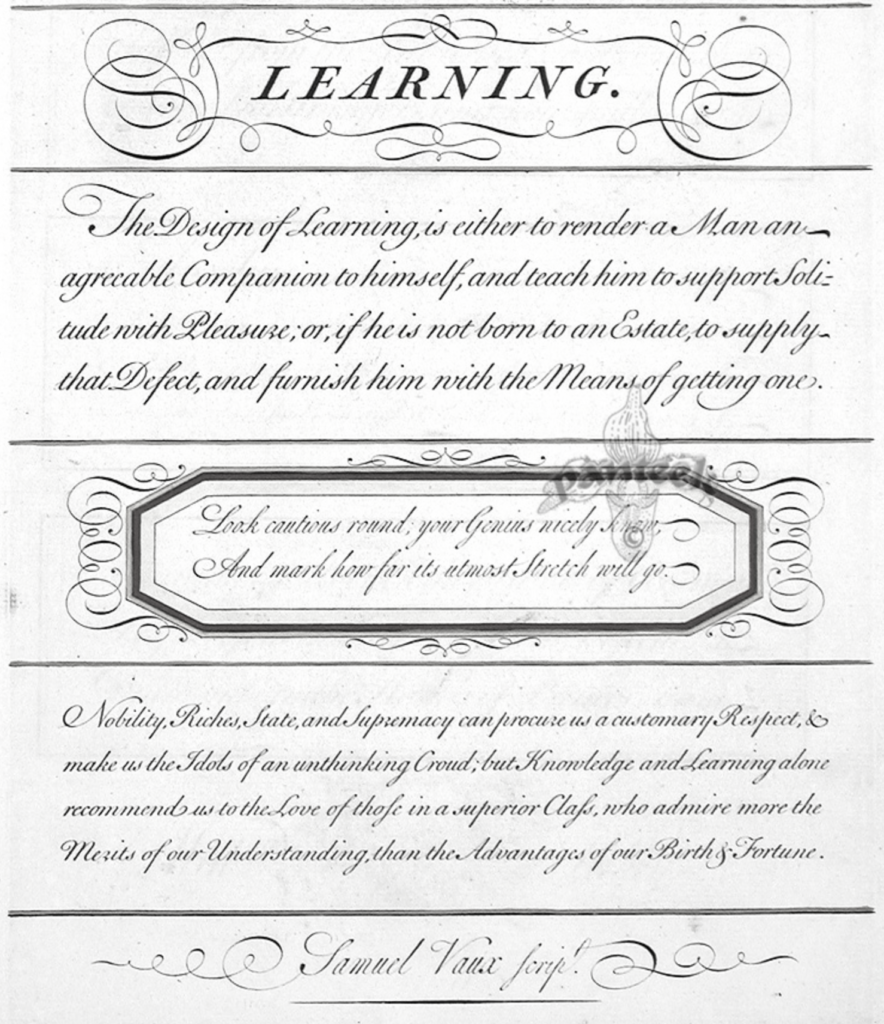

Copperplate, often used as an umbrella term for pointed pen calligraphy and once called English round hand, is a style of writing which emerged in the 18th century. Ornamental in style, the history of copperplate is linked to England’s status as an economic power, the rise of the business class and the rapid growth of commerce, all of which required scribes (read, white colonial men) proficient in writing and record keeping. Like crocus in spring writing schools sprang up everywhere, writing masters (yes, they were mostly white colonial men) flourished and published copy-books demonstrating their prowess at penmanship (Winters, 1989, pp. 12-13). These instruction manuals were reproduced by an engraver who would copy the writing master’s designs in reverse onto a thin sheet of copper called a plate using a sharpened steel tool, correcting imperfections, and making improvements to create script replete with intricate curls and elaborate swirls. The necessity for neat and accurate accounting had now become an art form. Between 1733 and 1741, master engraver and calligrapher George Bickham collected samples of writing artwork from 25 of the finest copperplate penman (yes, they were mostly white colonial men) and bound them in the book, The universal penman. Bickham’s book is still widely used today by writers and students of calligraphy, and I couldn’t resist taking a peek inside:

I also couldn’t resist hoping to find samples of artistic writing by women in Bickham’s book—but there are none. To be a woman in 18th century women in England was to have very little economic freedom. A woman was expected to “find a husband, serve them flawlessly, and reproduce” (Güven, 2022), and to confine herself to the private realm of home and family. Having confirmed her sole identity as the property of, and signed over all of her property to a prosperous man, she was not expected to have any hand in running the family business or to deal with any financial matters at all. Women therefore had no need to learn, become skilled or attain any form of “mastery” in copperplate writing. If they were asked or had any need to write a letter or correspond, they were expected to write in “ladies hand”, also known as the Italian hand. Italian hand was thought to reflect desirable female qualities such as gracefulness, lightness, subtlety, and legibility. The style of hand became code for who a writer was or wasn’t and what they did or didn’t do, and in this way, functioned as “subtle form of social control” to “keep people in their place” (Giaomo, 2016). In the case of women, these regulations speak to stereotypes of the 18th century which deemed them the “weaker” sex in brain, body, and soul and concerns about whether in fact they possessed enough concentration, intelligence, and physical strength to learn to write (or anything) at all. Seventeenth century English poet and writing master John Davies declared, “Never saw I yet a woman” who “could bruise a letter as men can do” (Sanders, 1998, p. 173) and firmly asserted the masculine authority of writing. The use of the word “bruise” by Davies is confronting and reminds me of Ursula Le Guin’s (1989, p. 169) indignation at the tendency in words and language used by men to lean towards battle, attack, conflict, and victory. If words are sentient beings, as Virginia Woolf suggests, to enact such violence on the letters which comprise their flesh and bones is unthinkable. My wonderings through all this writing about handwriting have left my head and heart tumbling up and down between themselves, thinking about the past in the present and the presents of the past. Like the writer herself, a woman’s handwriting was positioned then and there most appropriately as a decoration; and I wonder where that leaves both here and now.

Mistresses in the art of writing: Where are they?

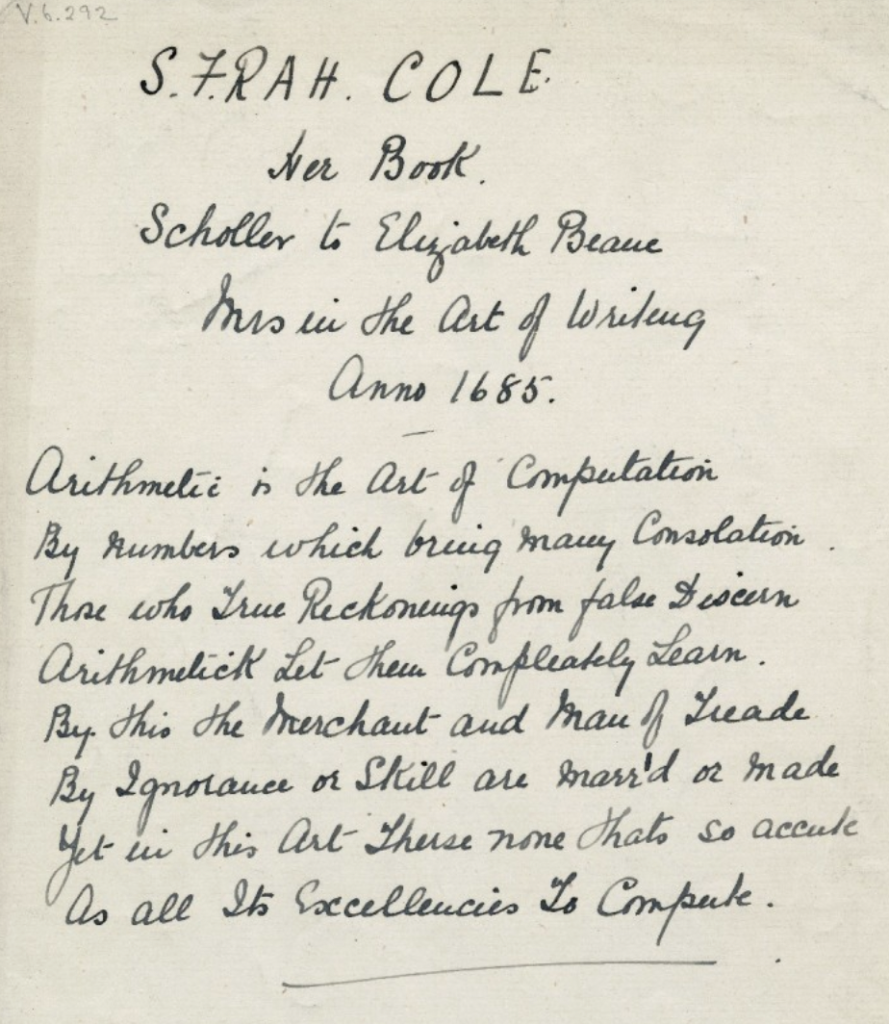

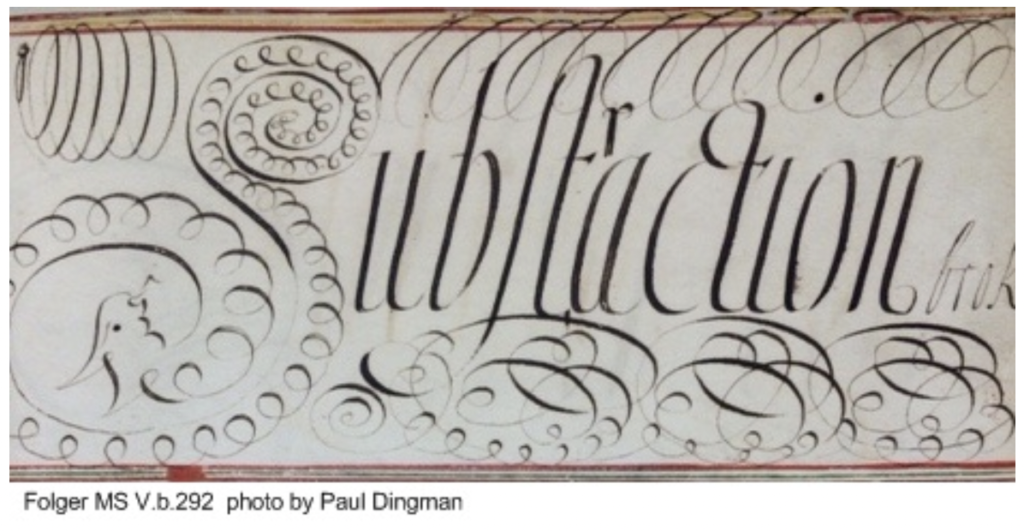

The absence of female calligraphers in Bickham’s book leads me on a historical search to find them. I find that outside of England (Wolfe, 2009), the art of women writing has a long and celebrated trajectory. I find Wei Shuo of the Eastern Jin dynasty in the 3rd century, credited with establishing the rules for regular Chinese script. In the 8th century I find Al-Shifa al Adawiyah (Tasnim, 2012), recognised as the first female teacher in Islam who taught the Prophet’s daughter to read and write. I find the “beautiful scribe” Diemoth (Beach, 2004) sequestered away in a Benedictine Bavarian monastery praying and transcribing valuable books of the 11th century. In the 15th and 16th century I find Dutch calligrapher Jacomina Hondius (Keuning, 1948), acclaimed as the first European woman to have examples of her work published. I find her compatriot Maria Strick and French writer Marie Pavie vying for the accolade of first woman to have authored a copy-book for commercial distribution. I find Elizabeth Pennington’s “Maidens Writing-School” in the 17th century England where “young ladies and gentlemen [were] taught the Arts of Fair Writing Arithmetick and True Spelling of English” (Wolfe, 2009, p. 25). I find the ornate arithmetic exercises dutifully copied by Sarah Cole under the tutelage of Elizabeth Beane, “Mistress in the Art of Writing”—her penning of “substraction” is as beautiful as it is delightful!

I find today that the art of calligraphy is increasing in popularity. A quick internet search for “calligraphy lessons near me” places “Pixiedust Calligraphy” as the number one pick—fellow lovers of lettering can enjoy a two-hour “Sip and calligraphy” class covering the basic tools and brush strokes techniques and time to experience the beauty of this art form. Another search for “famous female calligraphers” brings up a list of twelve influential women, posted on 9 and 11 March 2021 on a blog called “The Postman’s Knock” for International Women’s Day. The lettering of Pat Blair, Katrina Centeno-Nguyen, Shinah Chang, Younghae Chung, Suzanne Cunningham, Karla Lim, Kathy Milici, Schin Loong, Phyllis Macaluso, and Maureen Vickery is featured there, as is the work of Becca Courtice who donates the profits from her calligraphy classes to assist MS sufferers like her, and Amanda Reid who founded “Calligraphers of Color” to support and build a community for Black, Indigenous and people of color in this field. Picturing the ornate lettering we find on menu boards and shop signs, on the covers of books and movie screens, on wedding invitations and birthday cards leads me to think and wonder about whose writing is it? Whose hand created and styled those particular brush strokes?

Mistresses in the art of writing: Where are they?

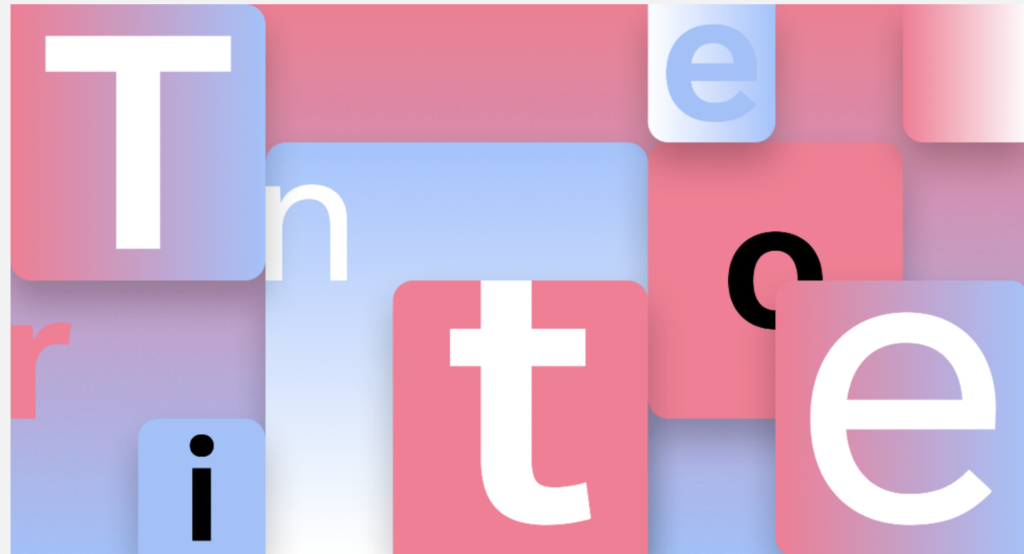

I then start to think and wonder, if we are not handwriting the words we write, we are most likely using the technology of a typewriter and/or keyboard to write, and rely on the font types provided to us by software developers to “pen” our words. It is easy to forget that before font types appeared in a drop-down menu on our computer screens, they were imagined and brought to life by hand—by a person holding a pen in hand and writing. I find myself searching then for font types by women and come across the University of Reading project Women in type which seeks to reveal the untold stories of female typographers. From their website I learn that the default font on Microsoft Word, Times New Roman was created by Dora Laing in 1931 while working as a “draughtswoman” for the British typeface company Monotype. Her work, however, is now credited to two men instead. On International Women’s Day in 2019, Protypr published an article titled “Typefaces created by women”. They reported that approximately 24.6% of popular Rentafont’s font collection (that’s 824 of 3346) are created by or co-authored by women. In 2021, Microsoft Word commissioned five new fonts to considered as the new default type face—first on the list is Tenorite by American female typographers Erin McLaughlin and Wei Huang which they describe as having the “look” of a traditional sans serif workhorse but warmer, wider and more friendly to read on screen.

This is now my default font on any Word document I type and there are so many others—Dover, Notable, Kotta One, Montaga, Sura to name a few—and the websites http://www.victoriarushton.com/fonts-by-women, http://www.alphabettes.org/resources/, https://fonts.adobe.com/collections/fonts-by-women, https://typequality.com/ and https://femme-type.com/ show case fonts by women and under-represented type face designers. The font I am using to write in-sister posts is “Sura” by Argentinian graphic artist and typographer Carolina Giovagnoli @larandg, a serif hybrid style typeface which received an award at the 2010 Ibero-America Design Biennial. If we think about the idea that writing in and out of hand embodies particular social and cultural codes and thereby “in-forms” our writing with particular kinds of powers, privileges and knowledges (yes, usually white, male, cis, hetero, able-bodied, and, and, and…), then the font type we choose to write with matters. Choosing to use typeface by women is me making a feminist investment in the creativity and careers of female typographers – after all, Hélène Cixous (1976) in-sistered that “woman must write herself” and “bring her body to writing”, which as I type this text, extends my female body writing to the woman’s body that created this type.

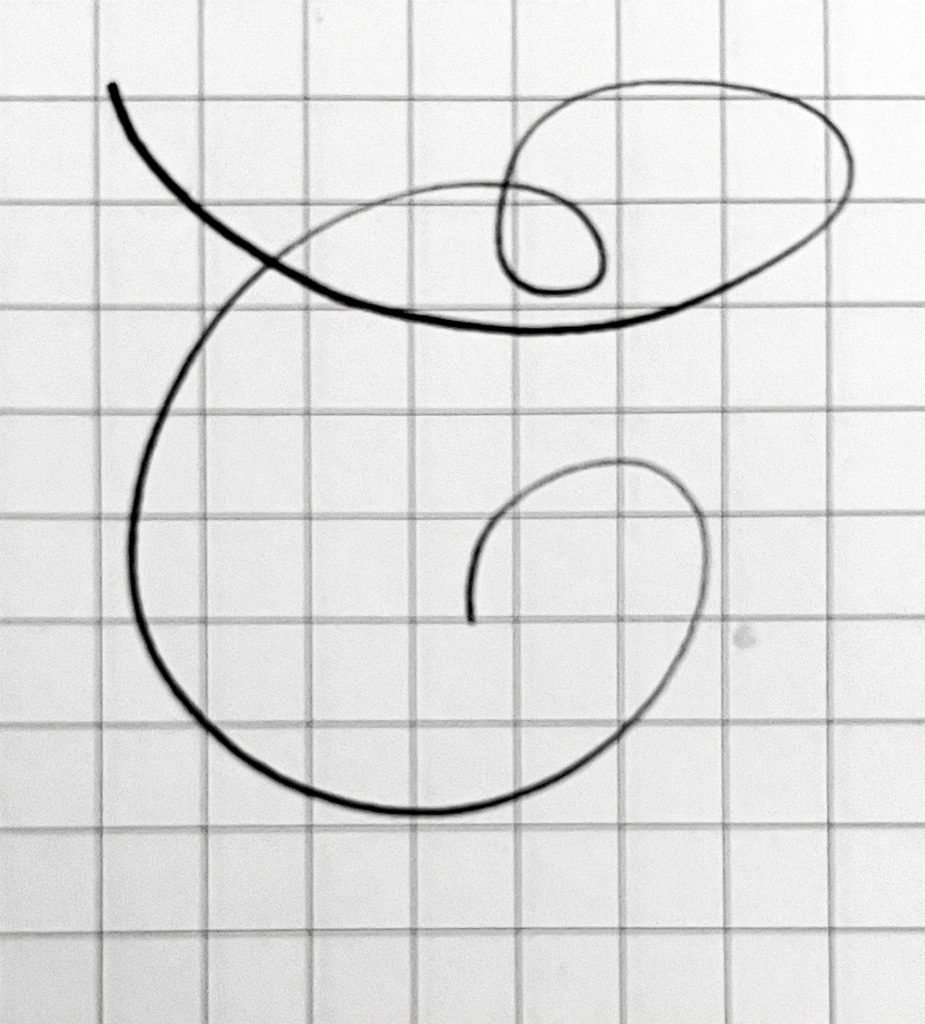

Like the flourishes of copperplate writing itself, this piece has followed its own flairs and flows of thinking and wondering about handwriting, the art of handwriting, and women’s handwriting that Natalie Goldberg’s work prompted. Since beginning this post, I have purchased an ink pen, all manner of calligraphy pens, a lettering practice book, and a step-by-step manual on how to “master” copperplate calligraphy. Each day I focus on one letter or a combination of letters, and lately I have been practising writing the entire lowercase alphabet without lifting my pen from the page. There is something quite liberating about just letting your hand flow from letter to another, letting the lettering feeling flow first to your hand and then to your heart—”handwriting is more connected to the movement of the heart” (p. 7) Natalie reminds me, so just “keep your handmoving” (p. 8) she says—just write, just keep your hand moving and let the letters run loose and long into words “with grace in and out of many worlds” (p. 56). With my heart and hand ready to tone up and tune into one another as we write, the only thing left to do is to sign off with a single letter at once fanciful and free, the letter

References

Alison Beach. (2004). Women as scribes: Book production and monastic reform in twelfth-century Bavaria. Cambridge University Press.

Hélène Cixous. (1976). The laugh of the Medusa. Signs, 1(4), 875-893.

Natalie Goldberg. (2016). Writing down the bones: Freeing the writer within. Shambhala Books.

Cara Giamo. (2016). The hidden messages of colonial handwriting: Back then, penmanship was basically secret code. Atlas Obscura, 6 May. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-hidden-messages-of-colonial-handwriting

Melis Güven. (2022). The status of women in 18th century English society. Arcadia [Blog post], 13 June. https://www.byarcadia.org/post/the-status-of-women-in-18th-century-english-society

J. Keuning. (1948). Jodocus Hondius Jr. Imago Mundi, 5, 63–71.

Ursula Le Guin. (1989). Dancing at the edge of the world. Groove Press.

Ruth Ozeki. (2013). A tale for the time being. Penguin Books.

Eve Rachele Sanders. (1998). Gender and literacy on stage in Early Modern England. Cambridge University Press.

Tasnim. (2012). Art of words: Women calligraphers then and now. Muslimah Media Watch, 6 February. https://www.patheos.com/blogs/mmw/2012/02/art-of-words-women-calligraphers-then-and-now/

Eleanor Winters. (1989). Mastering copperplate: A step by step manual. Dover Publications.

Heather Wolfe. (2009). Women’s handwriting. In The Cambridge companion to Early Modern women’s writing, Ed. Laura Lunger Knoppers. Cambridge University Press, pp. 21-39.

I loved this piece so much ! Its prompted me to drag out my copy of Natalie Goldberg and buy a journal and pen ! Weird, I cant find the tenorite font on my version of Word!

Thanks RR – pen and paper, the bend in the road to your heart lines ♥️ Jump on https://fontsfree.net to download Tenorite 😊

Beautiful, as ever! “…handwriting curls into curves at an entirely different pace…” mmmm. So true. Thanks for all that solid handwriting herstory xxx